The Right to Dream

Why rural women need permission to aspire

In the quiet villages of rural India, a powerful but often invisible struggle is unfolding — the battle to dream. Not the kind of daydreams we all drift into, but the radical act of imagining a life beyond prescribed roles, beyond marriage, beyond the unspoken limits drawn by gender and geography. At PCI India, we have come to believe that dreaming is not a luxury — it is the pillar of self-determination — and for millions of rural women aged 18 to 35, it is the first and often the hardest step toward meaningful workforce participation.

The Problem is Not Just Skills — It’s Permission

Much of the discourse on women’s economic empowerment begins with skilling and ends with placements. While these are critical, they assume that women are already in a position to want more — that they see themselves as workers, professionals, entrepreneurs, or change agents. But what if that vision is missing altogether?

In our experience, many rural young women are raised in deeply patriarchal settings where “ambition” is a word rarely associated with femininity. Household roles are normalized early. Work, if at all, is imagined as supportive — done at home, around domestic responsibilities, and preferably invisible. In such contexts, the ability to dream — to imagine oneself outside the frame — is not just missing, it is actively discouraged.

Aspirations are Shaped by What We See — and What We’re Told

Behavioral science offers us a compelling lens to unpack this. According to the aspirations window theory in behavioral economics, people tend to aspire only to what they see as feasible within their social context. If no one in a young woman’s world — not her mother, sister, teacher, or neighbor — has pursued a career or income-generating activity outside traditional norms, she is unlikely to view it as a viable path. Her window is small, her world tightly framed.

Economist Naila Kabeer has added that empowerment is not just about external resources but also about the “power within” — the ability to imagine choices, to articulate preferences, to see oneself as worthy of something more.

This internal power is precisely what we must cultivate.

A Field Story: The Silence Before the Spark

In one of our vision-building workshops in Jharkhand, a facilitator asked a group of young women what they wanted to become. The room fell silent. Not because they didn’t understand the question — but because no one had ever asked it before. Finally, one girl whispered, “Can I say something that’s not possible?”

This is the heartbreaking reality: dreaming is so far outside the norm that it feels like a violation of rules — an act that needs to be justified, negotiated, or hidden.

But when women begin to name their dreams, even tentatively, something shifts. In that same group, within two sessions, the room transformed. The quietest participants began sketching goals: to be teachers, nurses, police officers, business owners. The air filled with possibility. And that possibility — fragile but real — is what can ignite long-term change.

Dreaming Needs Scaffolding: Exposure, Safety, Language

If dreaming is constrained, it must also be enabled. It needs scaffolding.

At PCI India, our work in women’s empowerment has shown that dreams grow stronger when they are supported by:

- Exposure to role models — especially local women who’ve broken barriers.

- Safe, peer-led spaces where women can speak freely without fear of ridicule or reprisal.

- Language and tools to articulate one’s vision — including visioning exercises, journaling, and storytelling.

- Supportive family engagement, especially with mothers, fathers, brothers, and in-laws who may influence decisions around mobility, education, or work.

When these ingredients are present, we see not just a rise in confidence — but an expansion if ambitions.

The Unseen Rules that Contain Women’s Dreams

In many homes, a woman’s ambition is seen as a threat — to tradition, to hierarchy, to the established order. Aspiring to something different often triggers subtle (and not-so-subtle) sanctions: shame, gossip, ridicule, even violence. Dreaming disrupts the “normal.” It unsettles the norms.

This is where social norms theory — such as CARE’s Social Norms Analysis Plot (SNAP) — becomes useful. It helps us understand the invisible rules that govern women’s behavior, and the sanctions (gossip, shaming, violence) that follow when these rules are broken. Aspiring to something different often triggers these sanctions, especially when women are first-generation dreamers.

That’s why any program or policy that seeks to improve workforce participation must go beyond training. It must include behavior change communication, norm-shifting strategies, and family or community engagement — because no one dreams in isolation.

Intersectionality: Whose Dreams Are We Ignoring?

It is also critical to remember that not all rural women are the same. A Dalit woman in Bihar, a tribal girl in Jharkhand, a woman from religious minority group in Rajasthan — each faces layered exclusions. Their dreams are filtered through caste, religion, geography, and ability.

Dream-building must be intentional and inclusive — reaching those whose aspirations are most suppressed. One-size-fits-all doesn’t work when the systems of oppression are so diverse.

A Call to Action: Start with the Spark

What would change if we treated the ability to aspire as a fundamental right — not a luxury? What if, alongside every skilling or livelihood program, we embedded visioning, confidence-building, storytelling, and role model engagement? What if every intervention asked, not just what ‘can’ you do, but what do you ‘want’ to become?

At PCI India, we believe economic empowerment begins with mental permission. Skilling matters. So do jobs. But if a woman cannot see herself in a different future, she will never seek the path that leads there.

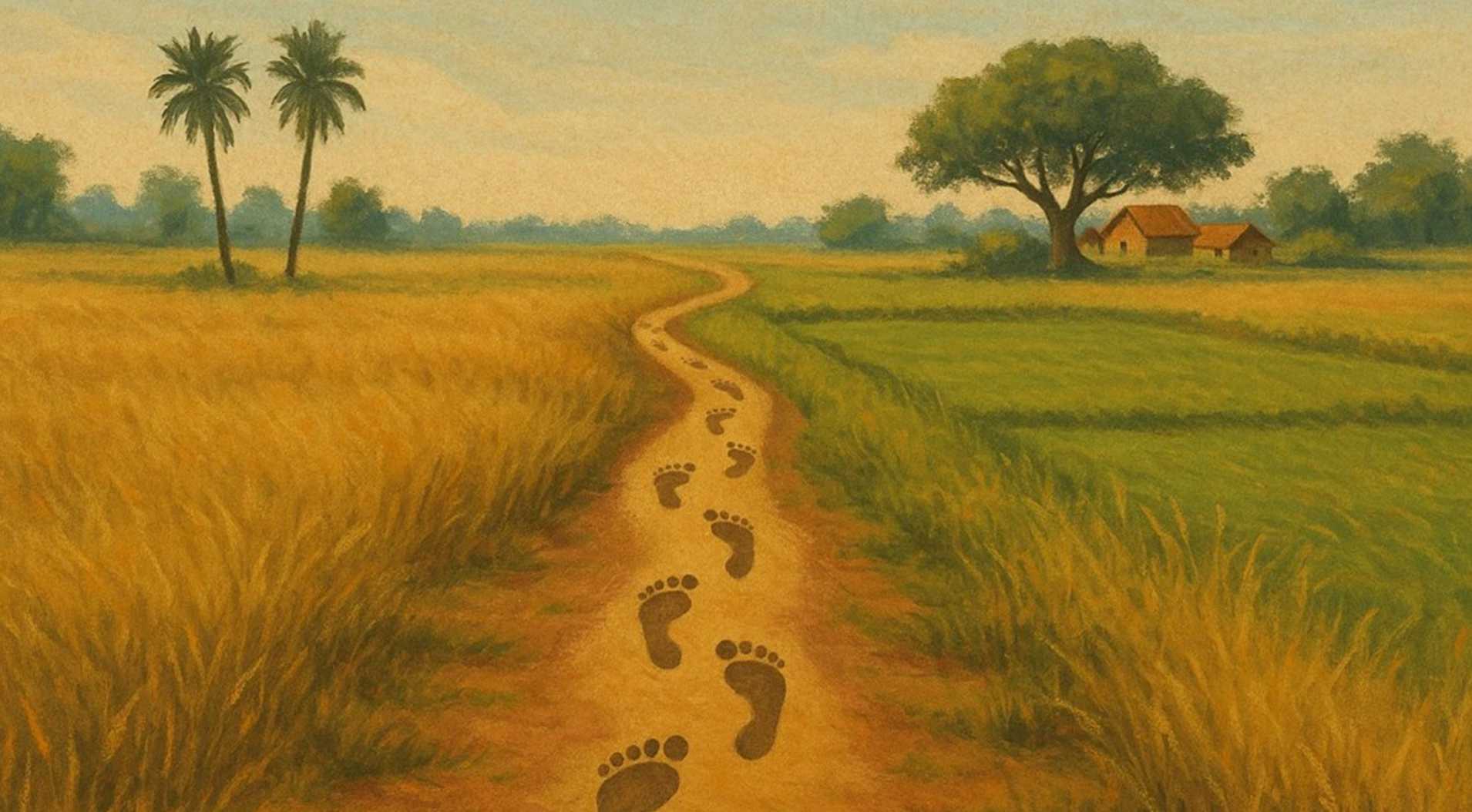

And so, our work must start not just with skills — but with spark. With dreaming. With helping women name the impossible — and then walk toward it, one step at a time.

Author: Sushmita Mukherjee, Technical Director – Gender, PCI India